|

trans·port

/tranˈspôrt/ verb

non·hor·mon·al

/nän-hȯr-ˈmō-nᵊl/ adjective

Useful Blog Posts

External Resources:

|

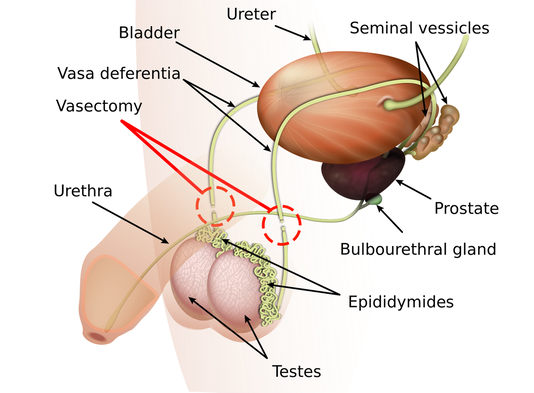

Sperm TransportAfter sperm are created in the testis, but before they demonstrate motility and fertilize an egg, they must be expelled by the body in a process called ejaculation. Upon ejaculation, sperm are moved from the epididymis to the vas deferens. From there, they move to the urethra before exiting the body. Preventing sperm from being transported out of the reproductive tract isn’t a new idea. In fact, it’s the basis of one of the only existing forms of male contraception – vasectomy.

In a vasectomy, the vas deferens are cut and tied, or sealed to prevent sperm from exiting the body. It’s a simple and effective process. Unfortunately, vasectomy reversal isn’t reliable enough for this to be considered a non-permanent method. Even if successful, vasectomy reversal is a time-consuming and expensive procedure, performed by specialists.

However, there are multiple groups working on reversible vasectomy, or what we call vas-occlusive devices. These devices work similar to a vasectomy, but instead of cutting the vas deferens, the flow of sperm is blocked with a substance that still allows fluid movement. Vas-occlusive devices are intended to be easily reversed at the user’s discretion. Some products such as ADAM™ and Vasalgel™ propose to do this either through natural degradation of the gel, or a simple restoration procedure. Male Contraceptive Initiative has funded ADAM™ and Vasalgel™ preclinical studies, and has also funded a clinical trial for ADAM™, where they look to evaluate their technology in men for the first time. Vas-occlusive devices can bring about a new long-term management of fertility for men – one that is reversible. These devices could act for years on end, and would require no maintenance or pill-taking on the part of the user. There are also pharmacological approaches to prevent sperm transport. MCI has funded Sab Ventura of Monash University in Australia to develop drugs that prevent sperm transport by blocking smooth muscle contractions. |

Male Reproduction & Contraception

The science behind male reproduction can be challenging, yet it is critical to understand the biology in order to know how the male contraceptives of the future will function. In an effort to make this science more accessible, we have developed a series of primers about male reproduction and contraception:

References

|

Waller D, Bolick D, Lissner E, Premanandan C, Gamerman G. Reversibility of Vasalgel™ male contraceptive in a rabbit model. Basic Clin Androl. 2017;27:8. Published 2017 Apr 5. doi:10.1186/s12610-017-0051-1

Cook, Lynley A; Van Vliet, Huib AAM; Lopez, Laureen M; Pun, Asha; Gallo, Maria F (2014). “Vasectomy occlusion techniques for male sterilization”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD003991. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003991.pub4. PMID24683020. |

Lohiya, N. K.; Manivannan, B; Mishra, P. K.; Pathak, N (2001). “Vas deferens, a site of male contraception: An overview”. Asian Journal of Andrology. 3 (2): 87–95. PMID11404791.

White, C. W., Short, J. L., Evans, R. J., & Ventura, S. (2015). Development of a P2X1-purinoceptor mediated contractile response in the aged mouse prostate gland through slowing down of ATP breakdown. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 34(3), 292-298. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.22519 |