|

By Tamiya Thomas, Environmental Steward and PMSC AmeriCorps Member at Three Rivers Waterkeeper Raccoon Creek Watershed As it rises in Washington County and drains north into the Ohio River from Beaver County, the Lenni Lenape granted the Algonquian name “aroughcoune”1 or Nachenum-hanne (“raccoon stream”) to what is known today as the Raccoon Creek tributary2. The Lenni Lenape relocated t0 western Pennsylvania as European settlers expanded across the east3, and lived among other tribes like the Shawnee “Woodland Tribe”. By the start of the 1700s, the Shawnee originally lived in the northeast including the Pennsylvania region and banks of the Ohio River. In the late 1700s, the Shawnee migrated westward to escape colonialism, and by 1832, the government removed the remaining tribe from the Ohio River Valley into Kansas4. Raccoon Creek lives in the Raccoon Creek Watershed, a network of creeks spanning 184 miles (including the west sector of Allegheny County)5. Ten miles from Pittsburgh, the watershed is witness to its industry boom in the 1700s and to its recreation restoration in the 1930s. Today, 32,000 people call the watershed and its valleys and woods home. The Raccoon Creek Watershed’s natural resources provide outdoor recreation for residents and visitors6. The natural resources lying beneath its surface also provide industries the opportunity to continue legacy production, discharge, and pollution in the same area. Industrial Development & ChangesThe Raccoon Creek Watershed lives in subbasin 20D within the Upper Ohio River. The lower two-thirds of subbasin 20D are characterized by round hills with narrow valleys and deep rivers. “Horizontal sequences of sandstone, shale, limestone, and coal from the Pennsylvanian Period” make up its rock layers7. These resources attracted farming and historical mining, and in 1781, Washington County encountered its earliest coal mining operations. The direct access to high quality coal led to the watershed’s restructuring as Pittsburgh hit its industrial boom. By 1840, railroads, locks, and dams were constructed to transport coal to Pittsburgh’s market. From 1880 to 1923, Washington County coal production reached a record high of 24.5 million tons8. The heavy industrial impact and over-used agricultural lands left Raccoon Creek land deforested and frail3. To reform the area to its natural state, the Recreational Demonstration Areas (RDA) selected Raccoon Creek as one of five conservation works in Pennsylvania. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and the federal Emergency Conservation Work Act transformed the non-sustainable land mass area into Raccoon Creek State Park. The park, 25 miles from Pittsburgh, offered outdoor recreation for large urban populations and offered economic opportunities for young men joining the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Between 1935 and 1941, the CCC and Works Progress Administration created picnic areas, roads and trails, the Upper Lake dam, quarries, and reforestation nurseries. In September 1945, the National Park Service transferred the park over to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania3. In tandem with the reformation, the U.S. Government purchased 305 acres of land in Potter Township to create a hidden high octane fuel depot, known as Tank Farm, between 1941 and 1942. The Department of Defense buried six 1.74 million-gallon fuel tanks and camouflaged the site as a farm to prevent air bombing9. The site pumped fuel through eight-mile underground pipes down to the Ohio River for transportation10 to assist in World War II. Eighteen years post-World War II, St. Joseph Lead Company acquired the land in 19639. The 1960’s marked a decrease in coal production overall, and in 1967, the total production accounted for less than 100,000 tons. While coal production significantly slowed down, commercial development pressures in the watershed grew rapidly with the commissioned residential infrastructures, Pittsburgh International Airport, and PA Turnpike Commission’s Southern Beltway linking I-79 to the airport. The shallow and deep wells leftover from the 19th century altered the watershed’s characteristics. Abandoned mine drainage, coal refuse, and industrial waste sites are the source of water quality and environmental issues for Raccoon Creek8. Modern Day Raccoon CreekFracking Currently, deep shale drilling is a popular industry method to extract oil and gas. The unconventional drilling method requires hydraulic fracturing (the horizontal “pulverizing of carbon-rich shales with water, sand, and chemicals”) to withdraw large volumes of resources. While hydraulic fracturing existed since the 1940’s, modern-day fracking is increasingly more water-intensive as it requires millions of gallons of water. According to the PA Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), there are 698 fracking wells in the Raccoon Creek Watershed. 214 of driller-reported wells use nearly 14.2 gallons of water per well. Fracking requires intense water pressure to fracture rock formations and extract oil and gas. Out of the 693 DEP published well locations, half are active (35% unconventional and 15% conventional), and the other half are not drilled (21%), abandoned or orphaned (20%), or designated as plugged wells (10%). The abandoned (not permanently plugged) or orphaned (no responsible operator on file) wells emit methane into the air and contaminate the soil and waterways with a mix of brine and oil. Fracking companies in the watershed include: Chevron, Range Resources, MPLX (Harmon Creek Gas Plant), the Revolution Gas Plant, and the Revolution Processing Facility.  Pipelines, old and new, run across the watershed to gather, transmist, and distribute oil and gas. Shell’s Falcon Pipeline transfers 107,000 fracked ethane barrels per day to the cracker plant in Potter Township; a 250 ft pipeline right-a-way runs from Clearview Road near Ambridge Reservoir5; and the Energy Transfer Revolution Pipeline transfers natural gas through its 40.5 mile pipeline to processing facilities in Allegheny, Beaver, and Washington Counties11. A landslide caused the pipeline’s “massive explosion and discolored the hillside near Ivy Lane in Center Township, Beaver County” seven days after the pipeline entered service. Energy Transfer’s pipeline owner illegally destroyed 23 streams and 1,900 feet stream channel loss with soil filling. In addition to nine environmental crimes and a $30 million fine, Energy Transfer was ordered to restore dozens of streams that may have contributed to the landslide5.(Image Courtesy of FracTracker Alliance5: shows discoloration of the hillside near Ivy Lane in Center Township, Beaver County)

Stewardship The Independence Conservancy, Three Rivers Waterkeeper (3RWK), Hollow Oak Land Trust are a part of the many organizations and volunteers protecting and restoring Raccoon Creek Watershed. The three non-profit organizations work with community partners to protect the health and beauty of Southwestern Pennsylvania’s water, land, and air. Independence Conservancy stewards the Raccoon Creek Watershed through education, conservation, and community partnerships12. The organization maintains the parking, trails, and accessibility to Raccoon Creek next to the Tank Farm Recreational Area and its water trail5. Following Horsehead Industries dedicating the tank farm to public recreation (2006), the Independence Conservancy acquired upstream and downstream land parcels for public access in 2009. The Department of Defense removed five of the six underground tanks in 2012, and Potter Township and the Conservancy gave a new life and purpose to the adjoining land areas. “With public grants, private donations, and plenty of volunteer muscle, the Conservancy has already restored hundreds of feet of collapsing creek bank, built a canoe/kayak launch, cleaned up tons of debris, planted thousands of trees, and created a new wetland brimming with wildlife”.10 Three Rivers Waterkeeper Styropek and Shell Polymers Monica (located on the Ohio River on either side of the Raccoon Creek tributary) are two major plastic production sources. On monthly nurdle patrols along the Ohio River next to Raccoon Creek, Three Rivers Waterkeeper and Mountain Watershed Association observed an excess of nurdles within the Ohio River. The two organizations traced the nurdles back to Styropek's main outfall (002) along Raccoon Creek, a major tributary to the Ohio River. This alleged illegal discharge of solid materials out of an outfall into a waterway was reported to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. In December of 2022, the PA DEP did a visual inspection at several of Styropek's outfalls and identified nurdles present near Outfall 002. The presence of these nurdles in the waterways was continued to be seen during the monthly nurdle patrols along the Ohio River and along Raccoon Creek. On December 5, 2023, PennEnvironment and Three Rivers Waterkeeper filed a federal lawsuit against BVPV Styrenics LLC and its parent company, Styropek USA, Inc. 3RWK is currently in negotiations, and hopes to see an outcome soon where Styropek is held accountable for their alleged plastic pollution13. In August 2023, 3RWK discovered Befesa Zinc US Inc.’s outfall 006 regularly violated permit discharge limits. Outfall 006 is associated with an uncovered landfill left over from a historic zinc smelter plant, and it flows into Raccoon Creek about less than a mile from the Ohio River. The outfall drains surface water with regular violations of selenium, manganese, and zinc from the old zinc plant. There have been 17 exceedances that include total selenium, total suspended solids (TSS), and total residual chlorine (TRC). From 3RWK’s YSI (our water quality measurement instrument) and laboratory samples, they discovered the results range from extreme acidic and basic pH levels. Under American Zinc Recycling, the company received monthly fines until June 2020. Since Befesa’s ownership, the company currently operates under an expired permit and administrative extension that prevents further fines from the DEP. The violations continued without any remediation actions being taken. 3RWK worried that if the site closed soon, the pollution issues would continue and remain unaddressed. On January 22nd, 2024, the DEP conducted a site visit in response to 3RWK’s complaints. DEP’s inspection report acknowledged the discharge monitoring report (eDMR) violations and stated that the site visit included a discussion with the personnel present: Eric Hunsberger, Director Environmental Affairs, Befesa Zinc US Inc.; Bob Orchowski, Environmental Consultant, The Hillcrest Group, Joe Pezze, Environmental Consultant, The Hillcrest Group; Stacey Greenwald, Clean Water Operations Group Manager, PADEP, Shawn Bell, WQS, PADEP. The discussion included possible compliance options, the status of the landfill closure, and a request for Center Township Municipal Authority to determine the possibility of sending discharge to the sewage treatment plant.

What’s Next for Turtle CreekConservation groups and volunteers will continue to steward and protect the watershed. The Independence Conservancy partners with Potter Township to create better accessibility to Rocky Bend Nature Preserve and its natural attractions.10 Three Rivers Waterkeeper, in partnership with the Mountain Watershed Association14, will continue to conduct regular nurdle patrols and water quality monitoring of the Ohio River in Beaver County. 3RWK will update the community when they conclude their negotiations with Styropek USA, Inc. and DEP’s solution recommendation for Befesa Zinc US Inc.Footnotes

0 Comments

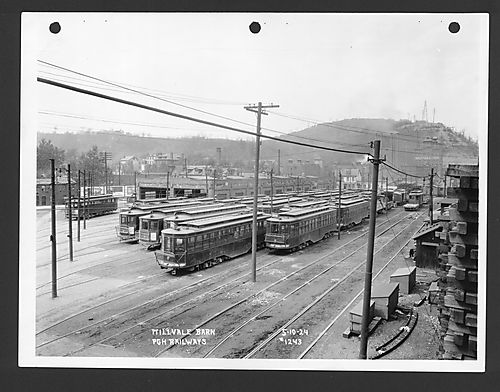

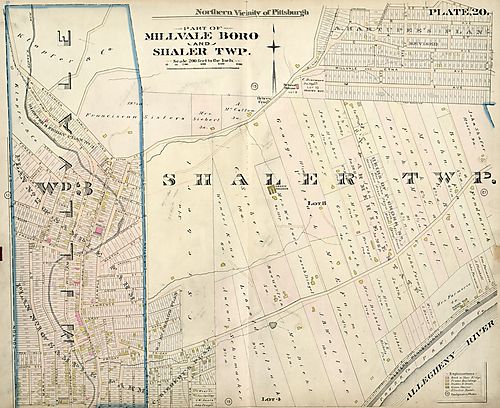

Written by Tamiya Thomas, Environmental Steward & PMSC AmeriCorps Member Overview About 27,000 people call the Girty’s Run Watershed home with highly urban areas, suburban commercials, and residential developments surrounding the land.1 Girty’s Run Watershed connects the townships and boroughs Shaler, West View, Ross, McCandless, Reserve, and Millvale2 and covers 13.4 square miles with approximately 28 stream miles.1 It’s a watershed on its way to a greener future as communities rally in the lower watershed portion for environmental sovereignty. A blog cannot contain the history overflowing within the watershed’s communities and tributaries. Members working and residing within the lower watershed provide wonderful and humbling insight into Girty’s Run and its community's hopes, fears, and dreams. The Girty Name Simon Girty Jr. was the second oldest son to Simon Girty Sr. of Scotch-Irish descent and Mary Girty of English descent. Simon had three brothers: Thomas Girty (oldest), James Girty, and Simon Girty. Simon Girty Sr. worked as a packhorse driver in addition to trading business. The trade negotiations could transform into brawls, and during a trade, Simon Sr. was stabbed and killed by “Fish”, a Lenape Native. In turn, John Turner, Girty’s half-brother, sought revenge and killed Fish. To make ends meet, Mary Girty married John Turner who moved the family to Fort Grantville to escape the encroaching French-Indian war. The Fort was overrun and burned to the ground by French and native forces on August 2, 1756. The Shawnees and Delewares took Mary and Simon’s brothers captive, and the Senecas took Simon (15 years old) and his stepfather into their captivity. The Senecas tortured and murdered John Turner for killing Fish.3 Seneca Chief Guyasuta adopted Simon, and for the next eight years, Simon traveled and learned the Seneca language and culture. The Seneca refer to themselves as O-non-dowa-gah (pronounced Oh-n’own-dough-wahgah) or “Great Hill People”. The Seneca cultivate Deohako (pronounced: Jo-hay-ko), “the life supporters”, known as the Three Sisters: corn, beans, and squash, as a primary food source in addition to hunting and fishing.4 The Seneca engage their lifestyle and culture in nature. They celebrate six major religious festivals in relation to their harvest: The Maple Festival, Planting Festival, Strawberry Festival, Green Corn Festival, Harvest Festival, and Midwinter or New Year's Festival.5 As a matriarchy, the women solely own the lands and homes, tend to the children6, and run the eight clan divisions: “in the first Moiety are the Wolf, Turtle, Bear, and Beaver; the second Moiety are the Heron, Snipe, Hawk and Deer”.5 While the clan mothers organize work by their clan, the male chiefs handle administrative work and diplomacy.6 The Senecas are renowned fierce adversaries highly skilled in warfare who engaged in diplomacy and rhetoric, and they joined five other indigenous nations to form the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) to combat the influx of European colonizers.4 During the Iroquois Wars, the Haudenosaunee and English colonizers remained allies until the Treaty of Paris 1763.7 As the war ended in 1763, “Chief Guyasta negotiated a treaty (on behalf of the Iroquois Confederacy) to release all white captives. In 1764, Simon and his family reunited in Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh) where Simon took an eleven-year translator position for the British and Native Americans. By 1775, Girty became a lieutenant for the Fort Pitt command. Under General Edward Hands’ command, Simon was heavily disliked by the commander. However, Simon was well liked among British and Natives alike and was publicly known to be against the Americans eliminating indigenous clans. General Hand saw the failed British-Native attack on Fort Henry as an opportunity to paint Simon as a traitor, and he called for Simon’s capture and execution. Fortunately, Simon was able to escape to the Ohio Valley with his three brothers. Simon returned to his role as a bridge between British and Native forces. When the American Revolution ended, the British Crown granted Girty land in Ontario for his services. The last few records of Girty maintain that he settled down and eventually passed from rheumatism.3 Other legends of Girty suggest he actually roamed with Native Americans as a band of looters and killers. The group roamed all over to steal and trade anything of value and peddled American scalps to the British for $10 apiece. Eventually, Girty betrayed his counterparts and ran off with their loot to bury it along the Allegheny River. The native clan planned an ambush on Girty, however, Simon was able to cross a creek bed in Ross Township and escape into Canada where he died. The creek was later named Girty’s Run after Simon though some historians believe the creek was named after his older brother, Thomas Girty.8 Thomas Girty was the oldest of the four Girty brothers, and he joined the American cause during the Revolutionary War. He opened a trading post along Girty’s Run following the murder of his wife, Ann Emmons Girty.9 The Girty Hill’s spot where Thomas settled his home is now known as Girty’s Run because of his residence and not because of the original family residence.10 Brian Wolovich, [insert credentials], spoke with two Thomas Girty family descendants (who still reside in Millvale) on the creek name. One member states, “I believe Thomas, but Simon used it, as many indigenous people, as a travel guide.” The second agrees that Thomas is the reason for the name, as he “had a trading post along it, however, the lore says Simon used it to escape and it was named after him”.11 Girty’s Run Industrialization Millvale When the Revolutionary War ended, John Sample received a land compensation award for his service in the Continental Army. His grandson built the stone house on the Sample Estate, and Allegheny County purchased 164 acres of the estate to establish a poor farm (an institution for poor and dependent persons) that sparked the industrialization boom. Most notably, Andrew Carnegie served as a bookkeeper at Henry Phipps’ rolling mill. After the mill’s twenty-threeyear run, Carnegie and Phipps founded Carnegie Still. By 1857, the Pennsylvania Railroad’s canal system purchase signaled Western Pennsylvania's iron horse revolution, and a population boost helped establish the Bennett and Company Railroad Station. Later, Graff and Bennett acquired Phipp’s mill and transformed it into the area’s first post office. With assistance from schoolteacher M.B. Lyon, Millvale Borough (a name reflecting its industry and landscape) emerged from parts of Shaler Township and Duquesne Borough on February 13, 1868.12 By the 1900s, “Millvale had annexed the Third Ward from Shaler Township and had three schools, three breweries, an opera house, a grocery store, a candy store, and a Masonic lodge". The Civil War and Millvale’s connection to Lawrenceville via the Ewalt Covered Bridge expanded the town’s population from its original number of 668. Graff and Bennet’s Mill became a car barn for the trolley system. Pittsburgh saw its first water and electric company, and by the quarter century, Millvale was bustling with local and industrial businesses. Millvale fortified Girty’s Run Creek to assist the World War II efforts through the town’s prosperous manufacturing businesses and communities. Unfortunately, Millvale’s war boom didn’t survive the energy crisis and loss of the manufacturing and steel industries.12 (First Image: Millvale Car Barn, #1243, May 10, 1924, image courtesy of Historic Pittsburgh)18 (Second Image: Part of Millvale Boro & Shaler Twp, 1897, image courtesy of Historic Pittsburgh)19 Girty's Run Flooding Girty’s Run Watershed’s “highly developed urban nature” historically results in intense flooding within the lower watershed region.14 The Girty’s Run Watershed municipalities reconstruction efforts to “control Girty’s Run intensified in the early-mid 1900’s”. On May 10, 1932, Millvale Borough, West View Borough, Shaler Township, and Ross Township collaborated in a thirty-inch joint trunk sewer line agreement.13 By 1956, the sewer line proved inefficient as Girty’s Run suffered from flooding in 195014, causing sewer and basement flooding. The October 1978 Stormwater Management Act (Act 167) “required counties to prepare and adopt stormwater management plans for each watershed to alleviate flooding”. Millvale Borough, Shaler Township, Ross Township, and Reserve Township formed the Girty’s Run Joint Sewer Authority (GRJSA) in June 1984. The organization serves and maintains the watershed sewer system to eliminate and prevent hydraulic overload in addition to meeting current and future demands of the watershed. By 1986, they adopted a Stormwater Management Plan in 1986 which was then updated in 2008*. In 1996, the GRJSA proposed a project (approved in 2001) to build one 3-million gallon tank in Bauerstown and one 5-million gallon tank in Ross Township.13 Alongside the municipality's reconstruction efforts, the Army Corps of Engineers built a 50-foot retaining wall to prevent erosion and improve drainage in the 1930s. The organization attempted to stabilize Girty’s Run in the 1980s, however, the gabion baskets meant to channel water failed during the Hurricane Ivan flooding in May 2004 and “devastated the watershed, particularly Millvale.” Hurricane Katrina halted government reconstruction support in 2005, and in August 2007, two flash floods hit Millvale within the same week. In response, the Army Corps of Engineers “dredged a six-mile stretch of Girty’s Run”.14 Shaler Township and Millvale Borough residents receive the brunt of the property damage from the flooding. Janet Zipf, a proud resident of Millvale for 50 years, reflects on the floodings and their impacts on the community. She owns three buildings with two located on Butler Street (including her Back to the Earth Healing Center). Janet’s parents purchased property back in the 70s, and Millvale wouldn’t experience another flood until Hurricane Ivan in 2004, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and two flash floods in 2007. Janet lost over $20,000 worth of items as the water came up to her doorstep and flooded neighbors. A majority of the community didn’t have flood insurance to cover the devastation. Janet recalls the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) coming to help, and she mentions FEMA was the only flood insurance available for purchase at the time. Janet lost over $20,000 worth of items as the water came up to her doorstep and flooded neighbors.15 Flood insurance is a requirement for mortgage renters while it’s optional for building owners, and if residents didn’t have it, they wouldn’t receive help. Over the past two decades, insurance company options increased, and it seems insurance prices increased right alongside it. Janet remembers only paying $400 to start off, and within two years, saw her rate increase to $500. As of two years ago, Janet used to pay up to $2,400 in coverage, and she only applied for the minimum to cover homeowner contents, cleanup, electric panel, water tank, and wall and floor damage including kitchen cabinets. Now, Janet pays another broker $1,800, and with her renewal coming up in spring, she’s nervous about the cost increase though remaining hopeful that insurance company competition will keep the cost rise to a minimum. Janet, like many of her counterparts, rallied at town meetings to create legislation for Girty’s Run. She’s met with senators, core engineers, and Brian Wolovich to discuss the future of the tributary. Janet will continue her support in flood management for Millvale.15 The Watershed Today Western Pennsylvania Conservancy Environmental organizations collaborate in green infrastructure to improve Girty’s Run. The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy prepared (WPA) The Lower Girty’s Run Watershed Conservancy and Management Plan to provide specific recommendations for implementing projects to help restore and protect the watershed.14 The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (WPC) is a member-based nonprofit organization in connection with cities, towns, and thousands of volunteers, partners, and volunteers across western PA. Since 1932, the conservancy has dedicated its resources to protecting and restoring the region’s natural places and its water, land, and life. This work benefits wildlife, people, and future generations that call Western Pennsylvania home.1

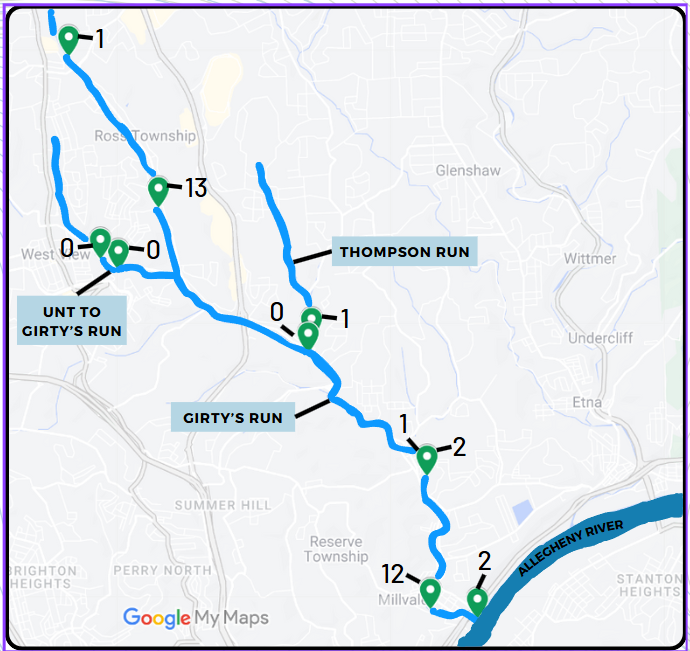

Three Rivers Waterkeeper Three Rivers Waterkeepers (3RWK) is a Pittsburgh local nonprofit organization protecting the Monongahela, Allegheny, and Ohio rivers - in addition to their respective watersheds - for safe drinking, fishing, and swimming. Founded in 2009, 3RWK is a scientific and legal advocate for the community as the “waterways are critical to the health, vitality, and economic prosperity of the Pittsburgh region and communities”. 3RWK monitors and tests waterways to ensure companies are in compliance with water laws and regulations. Water sampling provides integral information to determine water quality throughout the watershed. 3RWK continues to monitor E.Coli community samples within the Girty’s Run Watershed.

The testing did not conclude a single source for the contamination. The green location tabs mark the number of E.coli colonies found at each site. The Unnamed Tributary running into Girty’s Run dilutes the thirteen E.coli colonies flowing from Ross Township. The colonies remain almost non-existent in the Thompson Run tributary as it enters into Girty’s Run. At the Millvale point, the number spikes up to 12, and suggests the issues come from Girty’s Run directly or another tributary upstream.17 What’s Next For Girty’s Run As the communities and environmental partners continue to collaborate on watershed improvements, Girty’s Run's future is full of bright possibilities. Jeff Birghman admires the community engagement with the Watershed Project. So many community members want to address and resolve environmental problems. When asked about Millvale’s residents like Janet Zipf, Jeff admonishes that “communities don’t have to have the money but the will, and Millvale has that.” The townships in the lower Girty’s Run Watershed recognize that it takes concerted work overtime in laying the groundwork for plans and good engagement. Groups like the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Three Rivers Waterkeeper, the Allegheny Land Trust, and communities will continue to work to improve Girty’s Run Watershed and its neighborhoods. Resources

Tamiya Thomas

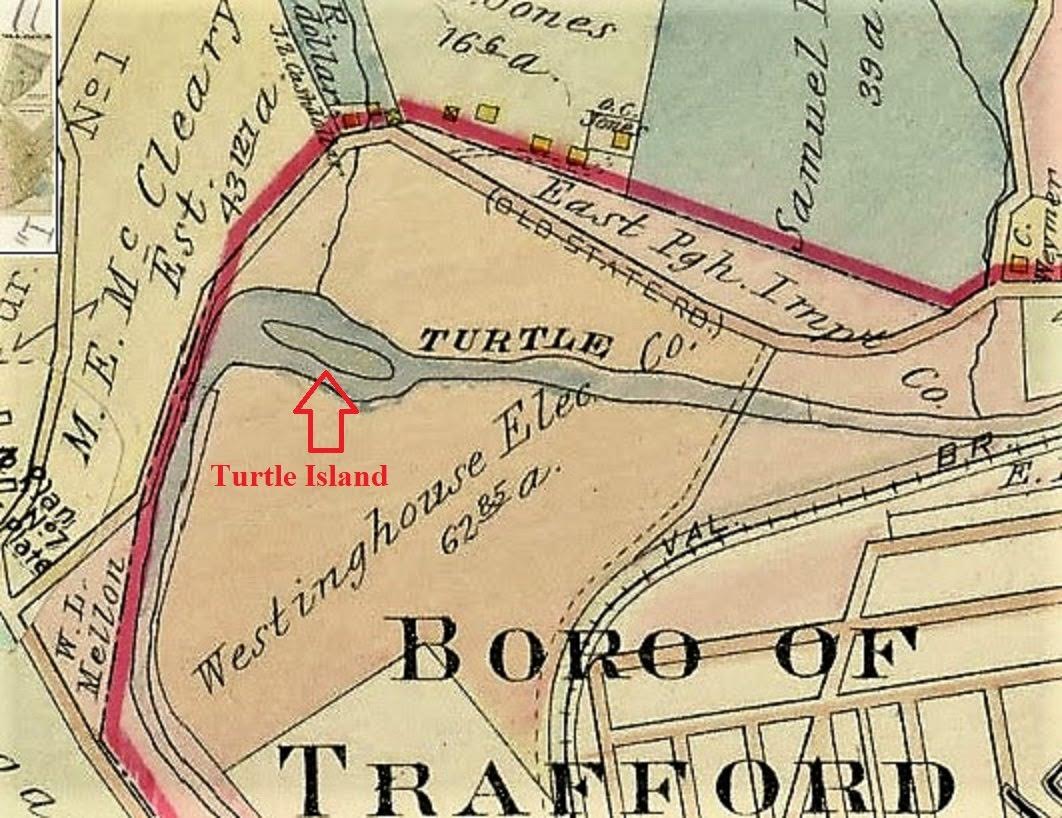

Tamiya Thomas is a graduate of PennWest University California ( Formerly California University of Pennsylvania) with a Bachelor’s in Business Administration and Management and minors in Musical Theatre and Tourism Events. She recently finished a three and a half month restoration project in Alaska! Through the Student Conservation Association program, she had the opportunity to camp in small town Hope, Alaska and revegetate Phase Two of the Resurrection Creek. These project phases focus on rebuilding the natural flow and flood banks of the river that were destroyed from decades of mining. Tamiya also worked with the U.S. Forest Service, contracted construction crews, and the town of Hope in restoring a beautiful landmark! Tamiya has interests in Performing Arts (singing, dancing, acting), Video Essays on pop culture and film media, Reading and Writing, Conservation, Interior Decoration, and Fashion Written by Tamiya Thomas, Environmental Steward & PMSC AmeriCorps Member The Turtle Creek tributary flows 21.1 miles through Allegheny and Westmoreland County. The tributary belongs to the Turtle Creek Watershed beginning in Delmont, PA before finishing its 147.41 square mile journey at its mouth in the Monongahela River. The Pittsburgh suburbs within Allegheny County and the communities in Westmoreland County “make up 33 municipalities, including two cities and eight townships, along with 23 boroughs, with the most area being taken up by Murrysville”. As urbanization and industrialization grew, human development has topographically altered the stream’s shape and aquatic life. Dams and abandoned mines contribute acid mine drainage to the watershed as fourteen species of concern living in the watershed, including five flora and nine fauna, suffer from poor water quality. In conjunction with water laws and water agencies, watershed organizations work to rehabilitate the Turtle Creek watershed [1]. Paleo Indian Period Three main tribes inhabited the Turtle Creek Watershed - the Monongahelas, Haudenosaunee, and the Turtle Clan of the Lenai Lenapi - with over 200 sites for large villages, farms, and campsites [1]. The Turtle Clan of Delaware Indians occupied Turtle Creek - originally named Tulpewisipu, or Turtle River - in the early 1700s after the Europeans took over their lands along the Eastern Seaboard” [2]. The Lenape’s seasonal campsites, hunting techniques, and resource management meant easy access to the small game in addition to the “large-scale agriculture… supplement[ing] their hunter-gatherer society”. The Lenape organized themselves through “shared cultural and linguistic characteristics” - the Musee, or Wolf Clan, occupied northern New Jersey, The lower Hudson Valley and New York Harbor in NY; the Unami, or Turtle Clan, occupied central New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania; and the Unalachtigo, or Turkey Clan, occupied southern New Jersey and the northern shore of Delaware [3]. The Monongahela Natives created a farming culture - raising corn, beans, and squash - on the watershed’s resources before displacement by the Iroquois in the early 1600’s [2]. The mid-18th century marked the transition from native habitants to European settlers. The Pontiac Rebellion - from 1763 to 1765 - was a native push against the British reign with the Turtle Creek Watershed and the confluence of Turtle Creek and the Monongahela River acting as critical points in the war. The Lenape staged a surprise siege against General Henry Bouquet’s troops at Fort Pitt which led to a two-day battle with an eventual British win and secure rule in Western Pennsylvania [1]. On July 9, 1755, the French and Delaware Indians defeated General George Braddock at the confluence of Turtle Creek and the Monongahela River; however, the British claimed victory at Bushy Run against the natives, therefore, opening of Western Pennsylvania for European Settlement [2]. Industrialization The early 18th century saw European settlers establishing residence along Turtle Creek. Located in modern day North Braddock on Turtle Creek’s mouth along the Monongahela River, in 1753, John Fraser’s Cabin served as an important landmark and trading post with frequent visits from George Washington [1]. Widow Meyer’s Tavern was a 300 acre of land - modern day Monroeville, but once Plum Township - granted to Martha Miers in 1787 [4]. At the mouth of Turtle Creek, the tavern transformed from a colonial trading post [4] to travelers’ favorite stopping place in the 1790’s between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh on the Pennsylvania Railroad [5]. In 1878, a natural gas well was drilled in Murrysville, PA next to Turtle Creek, and by the late 19th century, “the watershed region was known for its coal mining and natural gas resources” [1]. Turtle Creek Watershed Industrial Impact By the 1800’s, the Turtle Creek Watershed settled into a farming community with almost half of its natural landscape transformed into farmland and fields. The introduction of livestock, elimination of natural buffers and filters, and excess sediment began to significantly impair the creek’s health, structure, and water quality. Without vegetation growth along the stream, the creek’s banks become unstable, lose nutrients from fertilizer runoff, and cannot provide shade to cool the water for aquatic life. Additionally, livestock weight impacts the stream bank structure, and as they begin directly depositing manure in the water, the livestock presence increases the risks of injury and disease transmission between animals. Without secure stream banks, stormwater runoff from pastures, rooftops, and pavements increases the sediment erosion entering the stream channel [6]. The sediment erosion and waste in the watershed begins in Union County and flows westward into Allegheny and Westmoreland County and its tributaries. Brush Creek and Thompson Run are the principal tributaries draining into Turtle Creek with the former located in Westmoreland County and the latter in Allegheny County. Jeanette and Irwin Boroughs drain into the Brush Creek tributary, and at its junction with Brush Creek, Turtle Creek receives sewage from Trafford City, Pitcairn, Wilmerding, Turtle Creek, and East Pittsburgh. At the time of their operation, Westinghouse Foundry Company and the Pennsylvania Railroad Shops in Trafford drained its sewage and manufacturing waste into Turtle Creek as well [2].

Trafford Historical Society, elaborates on Westinghouse’s impact in the Trafford area [8]. “In the spring of 1888, the Turtle Creek Valley Railroad, headed by George Westinghouse, began construction of a railroad line” to supply gas drilling equipment “from the Pennsylvania Railroad main line in South Trafford to Murrysville” with further rail line extension to “Export, White Valley, Delmont, Slickville, and Saltsburg to bring the coal to the Pittsburgh market." In November 1888, the Pennsylvania Railroad purchased the Turtle Creek Valley Railroad and operated it until the 1950 era as a branch line. The Pennsylvania Railroad Company collaborated with George Westinghouse to provide transportation for Westinghouse’s Foundry. With the steam locomotives restricted to forward mobility with limited reverse function, the construction for the B.Y. (Blackburn Wye or Blackburn Y) Station on the Turtle Creek Valley rail line to act as a “wye” for locomotive return trips to Pittsburgh went underway [7]. To construct the Turtle Creek Valley rail line, the natural stream flow of Turtle Creek needed to change. With the constructed diversion now sitting “beyond the current split rail fence”, the water flow “makes a nearly 90-degree turn running next to the rail tracks… [therefore abandoning] the original creek bed”. The original creek path became shallow and transformed into a swampy area overgrown with vegetation and weeds, known as the greenie pond for locals; in 1995, the pond was dredged and filled in - now with a “solid rocked bottom" - and currently spring fed with a depth of 4 feet at the Eastern end and a 12-foot depth by its Pavillion [7]. Andrew Capets, author of Good War, Great Men and local historian at Trafford Historical Society, elaborates on Westinghouse’s impact in the Trafford area. Westinghouse purchased farmland to build its foundry and town. A large portion of the old Westinghouse property is now a brownfield where some of the farmland once used to dump ash (sand transformed into molds with black cinders leftover). Other portions of the property contain PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) once used by the Westinghouse Power Circuit Breaker Division [8]. Further Changes to Turtle Creek The Westinghouse Foundry Company (Trafford City), the Westinghouse Air Brake Company (Wilmerding), the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company (East Pittsburgh), and the Pennsylvania Railroad shops (Pitcairn) drained sewage and manufacturing waste into Turtle Creek. The creek was used to cool and condense large manufacturing plants along the stream; however, the large acid presence in the water created corrosive effects on boiler tubes and condensers [2]. The 1907 Second Annual Report of the Commissioner of Health raised concerns that industry drainage and municipality drainage would form undesirable sanitary conditions and characteristics for Turtle Creek. If all municipalities sought grants to drain in Turtle Creek, in conjunction with the industries, then the sewage in the drainage basin would overtax the stream's ability to dilute the sulfur inputs [9]. Therefore, a solution was needed to redirect sewage outside of the drinking water source. Despite Westinghouse’s private dams protecting the “lower Turtle Creek Valley against backwater flooding from the Monongahela River, up to 4 feet above that of the March 1936 flood”, a majority of the flood damages are concentrated around two major industrial plants occupying extensive reaches along both Turtle Creek and Thompson Run: Westinghouse Electric Corp. and Westinghouse Airbrake Co. However, the “completion of the Tygart and Youghiogheny Reservoirs on tributaries of the Monongahela River, upstream of the mouth of Turtle Creek” have diminished the need for the Westinghouse gates [10]. The Flood Control Act of December 1944 authorized a flood control reservoir project for the Turtle Creek Basin with the purpose of maintaining flood control, industrial water supply, and pollution abatement. The dam site “would be on Turtle Creek, about 2 miles above the junction of Brush Creek” with the head reservoir located at Murrysville, PA. Subsequently, the Pennsylvania Turnpike’s western extension was built through the Turtle Creek Reservoir Project’s authorization area. Additionally, “extensive residential and commercial developments have occurred in the reservoir area near its head at Murrysville” [10]. Modern Day Turtle Creek Turtle Creek Watershed Association Today, groups like the Turtle Creek Watershed Association (TCWA) work to clean and rehabilitate the watershed. Founded in 1970, TCWA sat at the front of “the modern environmental protection movement… [as] one of Pennsylvania's oldest and most established watershed associations”. The watershed continues to cover and drain over a 147-square-mile area through 33 municipalities in Westmoreland and Allegheny County with Turtle Creek beginning its more than 21-mile journey from Delmont to the Monongahela’s mouth in East Pittsburgh [11]. The TWCA commissioned a 2002 study with Civil & Environmental Consultants Incorporated to compose the Turtle Creek Watershed River Conservation Plan including previous and current watershed conditions assessments; watershed characteristics details in identifying stream pollutants; and plan of action recommendations to remedy the pollutants [12]. The plan highlights the 1989 major fish kill [12] in the Pennsylvania Approved Trout Water (ATW) - “a main stem of middle Turtle between the mouths of Abers Creek downstream to the mouth of Brush Creek” [2]. The severe drought between 1988 and 1989 in tangent with an above-average acid mine water input caused the severe pH depression (pH = 4.6) [2] and high levels of aluminum; subsequently, this killed “approximately 3,200 hatchery-bred brown trout (Salmo trutta) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), as well as 2,500 forage fish”. “The fish developed mucus over their gills, thus preventing the exchange of dissolved gasses and ions with the surrounding water,” and despite attempts to restock fish in 1991, another kill in 1993 “ceased stocking efforts until later when reclamation efforts were implemented” [12]. The TWCA also partnered with Westmoreland County “to address ‘the largest untreated abandoned mine discharge in Western Pennsylvania’: the Irwin (mine) Discharge. The mine will serve as the location of water treatment system(s) to effectively eliminate untreated mine water currently contaminating Brush Creek and turning it orange. In Western Pennsylvania, the mine discharge is the largest with an average of 9 million gallons flowing through the South Side mine drainage per day. The South Side mine drainage acts as “the primary discharge point for thousands of acres of abandoned underground coal mines in the central Irwin coal basin”. To address and access the mine pool, the Biddle Property is the most “cost effective, realistic, and preferred alternative to treat the Irwin Discharge”. The project’s success will restore “approximately 9 miles of Brush Creek from Irwin to Trafford and further downstream via Turtle Creek into Allegheny County” [13]. Three Rivers Waterkeeper (3RWK) is a Pittsburgh local nonprofit organization protecting the Monongahela, Allegheny, and Ohio rivers - in addition to their respective watersheds - for safe drinking, fishing, and swimming. Founded in 2009, 3RWK is a scientific and legal advocate for the community as the “waterways are critical to the health, vitality, and economic prosperity of the Pittsburgh region and communities”. 3RWK monitors and tests waterways to ensure companies are in compliance with water laws and regulations. Water sampling provides integral information to determine water quality throughout the watershed. pH levels below 6 and above 9 standard (std) units can negatively impact aquatic life reproduction, growth, and disease and death rates. Chloride magnesium levels (Cl- mg/L) above 100 mg/L can suggest industrial and urban waste drainage, and high chloride concentrations “in freshwater can result in organisms lacking the necessary nutrients, which can eventually lead to death” [18]. Community members can also get involved with 3RWK through their volunteer programs. These programs offer water safety and pollution education within Southwestern PA, and volunteers can learn how to identify and report water pollutants and their sources. What’s Next for Turtle Creek We can take steps to preserve the Turtle Creek Tributary by ensuring we’re mindfully engaging with our waterways. Sustainable engagement with our waterways can look like using and disposing of harmful materials properly; volunteering at local watersheds and environmental organization events; and educating our community on our water needs. Knowing our clean water laws also protects our water resources and uses. The PA Constitution Right to Clean Water states “the people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment”. Furthermore, Pennsylvania’s natural water resources belong to PA citizens of today and the future, therefore, it’s the Commonwealth’s responsibility to “conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people” [14]. The Clean Water Act of 1972 structures the regulation of pollutant discharge disposal and surface water quality standards [15]. Additionally, the Clean Water Act and Pennsylvania’s Clean Streams Law regulates and requires “the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to evaluate aquatic ecosystem integrity through assessments of physical, chemical, and biological characteristics” [16]. To report an environmental complaint to the PA Department of Environmental Protection you can submit a complaint online or by calling 866-255-5158. To report an environmental emergency to the PA Department of Environmental Protection you can call 800-541-2050. Remember to prioritize your safety when assessing pollution incidents, and if it’s a life-threatening emergency, contact 911 first. Three Rivers Waterkeeper is a resource for YOU. If you see water pollution, want help investigating or reporting a waterway related environmental concern, or want to learn more about threats and issues that we face please contact us by calling at 412-589-9411 or by emailing at [email protected]. Footnotes

Tamiya ThomasTamiya Thomas is a graduate of PennWest University California ( Formerly California University of Pennsylvania) with a Bachelor’s in Business Administration and Management and minors in Musical Theatre and Tourism Events. She recently finished a three and a half month restoration project in Alaska! Through the Student Conservation Association program, she had the opportunity to camp in small town Hope, Alaska and revegetate Phase Two of the Resurrection Creek. These project phases focus on rebuilding the natural flow and flood banks of the river that were destroyed from decades of mining. Tamiya also worked with the U.S. Forest Service, contracted construction crews, and the town of Hope in restoring a beautiful landmark! Tamiya has interests in Performing Arts (singing, dancing, acting), Video Essays on pop culture and film media, Reading and Writing, Conservation, Interior Decoration, and Fashion |

Archives

March 2025

Categories |

|

Founded in 2009, Three Rivers Waterkeeper serves as both a scientific and legal advocate for our waterways, holding polluters accountable and empowering communities to protect their right to clean water. Our work is grounded in research, policy enforcement, environmental justice, and education.

|

CONTACT US:800 Vinial Street

Suite B314 Pittsburgh, PA 15212 412-589-9411 (office) [email protected] SIGN UP FOR OUR MAILING LIST |

© Three Rivers Waterkeeper. All rights reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed